By Ann Baier, NCAT Sustainable Agriculture Specialist

Foreword: After the recent passing of her mother, Ann reflects on some valuable lessons and preparations, especially relevant in the time of a pandemic.

Building resilience in agriculture and communities is at the heart of our work at the National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT). For over 40 years and continuing in this time of the pandemic, we persist in agricultural endeavors that support just and ecological food and farming systems in the midst of racial and economic inequalities and the public health implications of COVID-19.

Unexpected things happen all the time, in food and farming businesses, and in life. For a farm business to be resilient amid the unpredictable, we develop risk management plans and integrated pest management strategies to minimize loss and weather adversity. We create standard operating procedures, food safety plans, quality control measures. We analyze hazards and address critical control points and develop recall plans. We buy insurance. We set emergency preparedness plans in place, considering regional probabilities of a wildfire, flood, earthquake, hurricane or tornado, illness, or death.

Each of us has some capacity to prepare, prevent, or mitigate unpredictable events that may or may not happen in life and business. We also need to prepare for the inevitable (death)—that which will happen; we just don’t know how or when. During a pandemic, we are slightly more aware of our mortality, that any one of us could suddenly reach the end of our life. Our lives, no matter how long they may be, are finite. Even though talking about death may seem difficult at first, preparing for its eventuality won’t cause it!

Last year, my women’s group began discussing aging. (We are all aging, no matter how old we are!) We committed to meeting regularly to support and inspire each other to prepare for life’s eventual end. Each month we address a topic, such as Health and Medical Care, Legal Arrangements, Information for Survivors, Legacy / Succession, and Death Cleaning. We share meaningful reflections, practical help, and even laughter as we work toward clarity and organization. Our experience may be helpful to others.

The best time to make emergency preparedness plans is before the emergency begins. I’ll gather my important papers, map out an escape route, decide on an out-of-state contact and a family gathering place before a disaster looms and communications are lost. The best time to prepare to die is while we are healthy and of sound mind. When the possibility of illness and the eventuality of death seem far-off in the future rather than imminent, I can work with a clearer mind, and ground my decisions in carefully considered and dearly held values. It is quite all right to set arrangements in writing and not need them; it is more costly, legally complex, and emotionally exhausting to need, and not have them. Putting my affairs in order can give me peace of mind while I’m alive, especially understanding how I can minimize the legal, financial and emotional burdens on my loved ones–or business partners–when I cross life’s finish line.

Part I: Health and Medical Care: Advance Health Care Directives

My Mom used to joke, “None of us is going to get out of here alive!” Indeed, she made a timely exit from her life’s journey earlier this year. Her passing was peaceful and consistent with her values, thanks to her preparations. Mom completed both an Advance Health Care Directive (AHCD) and Physicians Orders on Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form, I had copies, and both documents were on file with her health care system. Mindful that someday she would take “that journey that needs no baggage,” my Mom had put her wishes in writing years prior when thoughts of physical frailty or mental incompetence were merely hypothetical.

No matter my age or current health status, I can consider various scenarios and write down my wishes. What if I get into an accident or fall suddenly ill, get a brain tumor, or lose my memory? There are times when discussing the real possibility–or probability– of disability or death might feel like taking away someone’s hope. It is best to prepare now, while I can still reason clearly and speak for myself. Knowing I have discussed my values and criteria for decision-making with my family and my doctor and filed my advance health care directive with my health care system, I can be at ease.

My Mom had a fall. At age 95, it was not her first, but this one was different. The doctor who assessed her condition asked if we wanted to honor my mother’s POLST. “Yes,” I said, knowing we’d had the necessary conversations ahead of time. “Then we are providing comfort measures.” I clarified, “This may lead to the end of her life?” “Yes.” Having Mom’s wishes in writing gave me peace of mind. I did not need to second-guess, or worry that a family member would question her end-of-life care. It also allowed her a natural death, free of invasive medical interventions. She was able to die as simply as she lived, with modest use of finite medical resources.

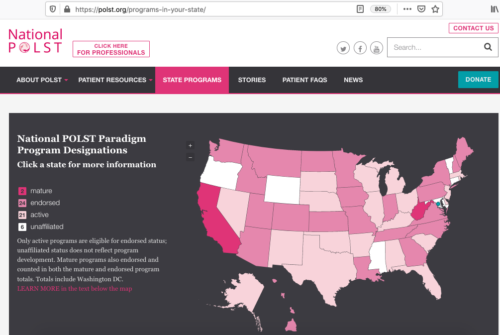

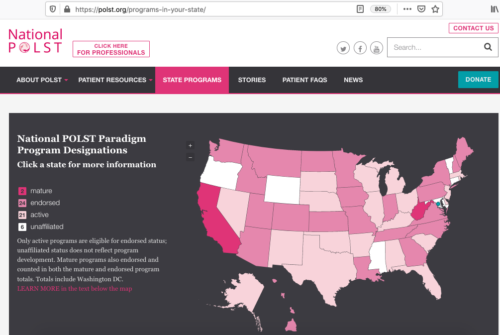

Advance Health Care Directive templates are easy to find; many health care systems provide them. Physicians Orders on Life-Sustaining Treatment, or POLST, is described in https://polst.org/: “All adults should have an advance directive to help identify a surrogate decision-maker and provide information about what treatments they want for an unknown medical emergency. A POLST form is for when you become seriously ill or frail and toward the end of life. A POLST form does not replace an advance directive — they work together.” The POLST form has three sections with checkboxes to express your wishes with respect to: A) Resuscitation (Attempt or Not); B) Medical Interventions (Full, Selective or Comfort-Focused Care); C) Artificially Administered Nutrition (Long-term, Trial or None), followed by D) Information and Signatures—yours and your doctor’s. That’s all. Together, the AHCD and POLST can save costly confusion for family members and care providers when life hangs in the balance. It is reassuring to have written guidance about when to try what kinds of interventions, and when to accept death when it is time.

Part II: Legal Affairs

Making legal arrangements, appropriate to one’s family composition and farm business, is a worthy investment of time and money. Get reliable legal advice! Key documents often include a Will, General Durable Power of Attorney, and a Living or Revocable Trust. A Trust complements the Will, and allows the property to be transferred to beneficiaries without the expense and delay of probate court proceedings. A Trust is “funded” by titling items of value (such as bank accounts and real property) in the name of the Trust, and recording deeds with the county.

A Trust names beneficiaries and Successor and/or Co-Trustees. “We wouldn’t want to declare you incompetent!” explained my Mom’s estate attorney, as she drew up the Trust. And explained the key distinction between Co-Trustee and Successor Trustee. Being named Co-Trustee gave me the legal authority to take care of Mom’s affairs as her energy waned, her eyesight faded, and her hand grew increasingly unsteady over several years. The latter would have allowed me to act only if and when the primary Trustee was declared physically or mentally incapable by a medical professional. Because life provides no guarantees about a person’s longevity or the order of death (one of my mom’s children died before she did), it is good to name more than one Co-Trustee, and the order in which they would serve.

Making necessary legal arrangements does not mean giving up or losing hope. It’s simply a good idea. At any moment, I may find myself needing to act, in some legal capacity, on behalf of my spouse, sibling or business partner—or one of them for me! Some people lose capacity gradually, with age or dementia; others more suddenly, due to an accident, stroke, heart attack, or some rapidly progressing illness. Human beings may find it increasingly embarrassing, frightening, or uncomfortable to speak of getting one’s affairs in order when failing health or death become real possibilities. Anyone’s judgment can be clouded by emotion, fear, or stress when the balance of life itself or the future of business seem to hang on some critical decision. Why not set things in order now?

Further Reading:

- Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande

- Get It Together: Organize Your Records So Your Family Won’t Have To by Melanie Cullen, September 2018, 8th Edition, NOLO Pres

Maynard says when she set out to launch her alpaca farm, she had no idea of the sustainable agriculture resources and farmer-veteran community that already existed. “When I came on to my land, it wasn’t in great shape,” she says. “I overgrazed my fields when I first started. I didn’t know how to manage ruminants correctly. ATTRA gave me the tools I needed to be able to do that. Not only did my land rebound, but the forage production per acre has at least doubled if not tripled because of the resources ATTRA empowered me with. I am now able to grow much more with less.”

Maynard says when she set out to launch her alpaca farm, she had no idea of the sustainable agriculture resources and farmer-veteran community that already existed. “When I came on to my land, it wasn’t in great shape,” she says. “I overgrazed my fields when I first started. I didn’t know how to manage ruminants correctly. ATTRA gave me the tools I needed to be able to do that. Not only did my land rebound, but the forage production per acre has at least doubled if not tripled because of the resources ATTRA empowered me with. I am now able to grow much more with less.”

The professionals have other tools, like a starch test and a refractometer for measuring sugars, but even the pros will use the four other indicators listed above.

The professionals have other tools, like a starch test and a refractometer for measuring sugars, but even the pros will use the four other indicators listed above.